Lost

The lost artwork of the Second World War represents one of the most devestating cultural losses in modern history. Under the Nazi regime, orchestrated looting, confiscation, and forced sale of art, particularly from Jewish collectors, ran mostly unchecked. Among the now most infamous figures linked to this history is Hildebrand Gurlitt, a German art dealer who played a central role in this cultural displacement. Operating within official Nazi commissions and on the margins of the art market around Europe, Gurlitt's work was largely forgotten until 2012, when over 1,200 works were discovered in the Munich apartment of his son, Cornelius. Not all of the artworks exhibited here are from the rediscovered Gurlitt collection, but are all in some way connected to the dark legacy left by Hildebrand Gurlitt. Each piece linked to Gurlitt reflects not only aesthetic value, but also the unresolved histories and personal traumas left in the wake of wartime looting.

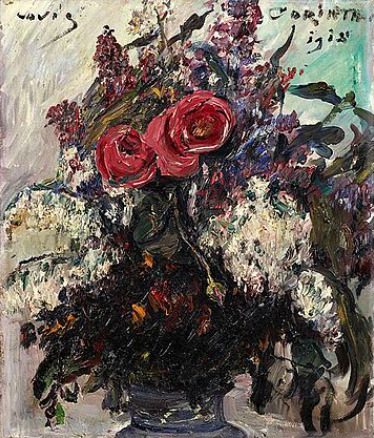

'Chrysanthemums' by Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), c.1914

Lovis Corinth’s Chrysanthemums (c.1904) is one of thousands of artworks believed to be lost through Nazi looting. This painting is known only through a black-and-white reproduction drawn by Charlotte Berend-Corinth (widow of Lovis and a painter in her own right) which was originally published in a 1958 catalogue of his work. The original painting was once owned by Sigmund and Agathe Fischbein, close friends of Corinth and part of a network of Jewish collectors in Germany during the 20th century. Their daughter Vilma Kristeller and her husband Walter later inherited their collection, including Chrysanthemums.

Due to escalating antisemitic persecution and the remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936, the Kristellers prepared to emigrate to New York. In September of the same year, Vilma and Walter Kristeller entrusted the Berlin-based transport company Gustav Knauer to ship their belongings once they arrived and settled. The couple emigrated on 22 October 1937, and their belongings arrived in May 1938. However, multiple pieces of art, including Corinth’s Chrysanthemums, were missing.

This is not an isolated theft. The Gustav Knauer company is now known as an accomplice in theft from the Jewish families who hired them and acted as an art transporter for the Nazi Regime during the length of the war. With links to art traffickers such as Hildebrand Gurlitt and Theo Hermsen, it is likely that the stolen artwork from the Kristeller family made its way through Nazi-art trade networks into private collection. Archival evidence shows that other Corinth paintings owned by the Kristellers (i.e. Roses and Lilacs, c.1918, shown below) were also stolen and sold by the Gemälde-Galerie Carl Nicolai on 10 February 1937. That painting resurfaced at the Van Ham Auction House in 2015, and their provenance research led to its restitution to the Kristeller heirs, which provides a compelling narrative for what may have happened to Chrysanthemums.

Without Charlotte Berend-Corinth’s reproduction and publication, no form of Chrysanthemums would exist in public memory today. The digital image of the painting does not replace the original, with its original characteristics like color, texture, and shading missing from its reproduction. As the sole visual record of the painting, researchers are able to engage with a work that has been physically lost, and its digital form becomes a vital channel for research, remembrance, and hopefully future restitution.

Sources:

Berend-Corinth, C., 1958, ‘Die Gemälde von Lovis Corinth’, Werkkatalog, München

“Chrysanthemums.” Chrysanthemums | Lost Art Database, www.lostart.de/en/lost/object/chrysanthemums/567066?term=lovis+corinth&filter%5Btype%5D%5B0%5D=Objects&position=12.

“Provenance Revealed: Provenance Research in Practice.” – Karl & Faber, 13 Oct. 2023, www.karlundfaber.de/en/2023/10/provenance-revealed-provenance-research-in-practice/.

Hoffmann, Créé par Meike. “Gurlitt Hildebrand (EN).” Accueil, http://agorha.inha.fr/detail/945

“Kristeller Collection-Van Ham Restitutions.” Kristeller Collection, Van Ham Auction House, www.van-ham.com/en/discover/van-ham-restitutions/kristeller-collection.html

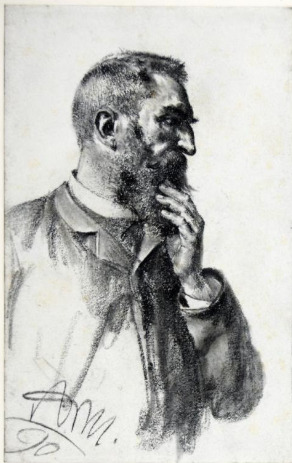

'Bust of a Man, who grasps his beard with his left' by Adolph Menzel (1815-1905), c.1890

Adolph Menzel’s Bust of a Man, who grasps his beard with his left (c.1890) is a graphite drawing outside the Gurlitt Collection whose provenance gaps leaves it hanging in limbo between lost and found. Registered within the Lost Art Database, the piece is documented as a found-object by the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD), specifically its Kupferstich-Kabinett, though no reproduction is publicly available in their digital collection.

The known provenance provided by the report traces its earliest ownership as the 1944 acquisition by Theo Hermsen in Paris, a Dutch art dealer historically implicated in art trafficking for the Nazi regime. Hermsen was well-known within the Kustkabinett, a Nazi-organized system used to acquire and display stolen art from Jewish collectors. From there, the drawing entered the possession of Hildebrand Gurlitt, who was a central figure for the Sonderauftrag Linz, or ‘Special Commission Linz’. Gurlitt worked closely with Hermann Voss to acquire artwork for Hitler’s unrealized Führermuseum, but it is unclear if Gurlitt ever delivered Menzel’s piece. If the drawing was ever officially given to Linz, it was not documented in its provenance. Its current place in SKD’s Kupferstich-Kabinett, but undisplayed in its digital collections, suggests that it's unclear origins prevent public access, and its absence illustrates the continued ambiguity surrounding many artworks during this period.

Menzel’s Bust of a Man occupies a distinct space as not fully lost but not entirely accessible. Officially listed as a ‘found object’, the work’s ties to the Special Commission Linz and art traffickers like Gurlitt and Hermsen place it solidly within the realm of ongoing research. Its absence from the SKD’s digital collections could reflect a hesitation to display a work with unresolved provenance, or it could simply be marked as a low priority for digitization. In contrast to pieces like Corinth’s Chrysanthemums or Kollwitz’s Mother with Dead Child, where its reproductions allow for engagement and access, Bust of a Man stands as an example of what happens when documentation and digitization remains limited. Its inclusion on the Lost Art Database signals ongoing work into its acquisition, but the lack of wider institutional acknowledgement limits its potential for research and possible restitution.

Sources:

“Bust of a Man, Who Grasps His Beard with His Left.” Bust of a Man, Who Grasps His Beard with His Left | Lost Art Database, www.lostart.de/en/found/object/bust-man-who-grasps-his-beard-his-left/569046?term=menzel&filter%5Btype%5D%5B0%5D=Objects&start=140&position=142

Leifeld, Markus, and Britta Olényi von Husen. “Theo Hermsen Jr.: Ein Niederländischer Kunsthändler Zu Zeiten Der Besatzung in Paris.” Transfer – Zeitschrift Für Provenienzforschung Und Sammlungsgeschichte | Journal for Provenance Research and the History of Collection, http://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/transfer/article/view/91513

Database on the Sonderauftrag Linz (Special Commission: Linz), www.dhm.de/datenbank/linzdb/einleitunge.html#Zur_Geschichte_der_Linzer_Sammlung_.

“Provenance Research - Artworks for the „Linz Special Commission": SKD - Multimedia Guide.” SKD, http://guide.skd.museum/en/Tour/Object?guideId=930&objectId=81718.

'Palatinate landscape' by Max Slevogt (1868–1932), undated

Pfälzische Landschaft (Palatinate Landscape) is an undated oil painting on cardboard by Max Slevogt (1868–1932), a leading figure of German Impressionism. Known for his expressive brushwork and luminous depictions of the German countryside, Slevogt considered the Palatinate region his spiritual and artistic home. This landscape, painted in muted tones and populated only by circling birds and distant trees, reflects his lyrical vision of solitude and natural rhythm.

Yet the peaceful scene belies a turbulent history. The painting once belonged to Eduard Fuchs, a prominent Jewish intellectual, art collector, and political writer. In 1933, following the Nazi rise to power, Fuchs’s collection was confiscated by the Gestapo. To pay the Reich flight tax, Fuchs’s daughter Gertraud was forced to sell the rest of the art from the collection in 1937–1938.

Pfälzische Landschaft was auctioned at Rudolph Lepke’s Berlin auction house on June 16–17, 1937. Despite competition from the collector Franz Josef Kohl-Weigand, the painting was acquired by the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt for 160 Reichsmarks. Gurlitt annotated his copy of the auction catalogue and later confirmed the purchase in a handwritten note from 1938, explicitly identifying the work as coming from the collection of “the well-known Jewish writer Eduard Fuchs.”

Since then, the painting’s location has remained unknown. It is registered as Nazi-looted cultural property in the Lost Art Database and is considered missing.

Pfälzische Landschaft stands as both an artistic document of Slevogt’s intimate connection to the Palatinate landscape and a silent witness to the forced dispossession of Jewish collectors under the Third Reich. Its unresolved fate exemplifies the ongoing work of provenance research and the ethical imperative to reconstruct and acknowledge histories of cultural loss.

Sources:

Lost Art Database. “Palatinate Landscape by Max Slevogt (Lost Art-ID 589423).” Stiftung Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste, https://www.lostart.de/en/lost/object/palatinate-landscape/589423?term=Hildebrand%20Gurlitt&filter%5Btype%5D%5B0%5D=Objects&start=60&position=73.

Stiftung Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste. “Object Record: Pfälzische Landschaft, Max Slevogt (PDF Documentation, Lost Art-ID 589423).” Accessed via Lost Art Database, https://www.lostart.de/sites/default/files/attachment/document/2024-01/eobj_589423_79542.pdf.