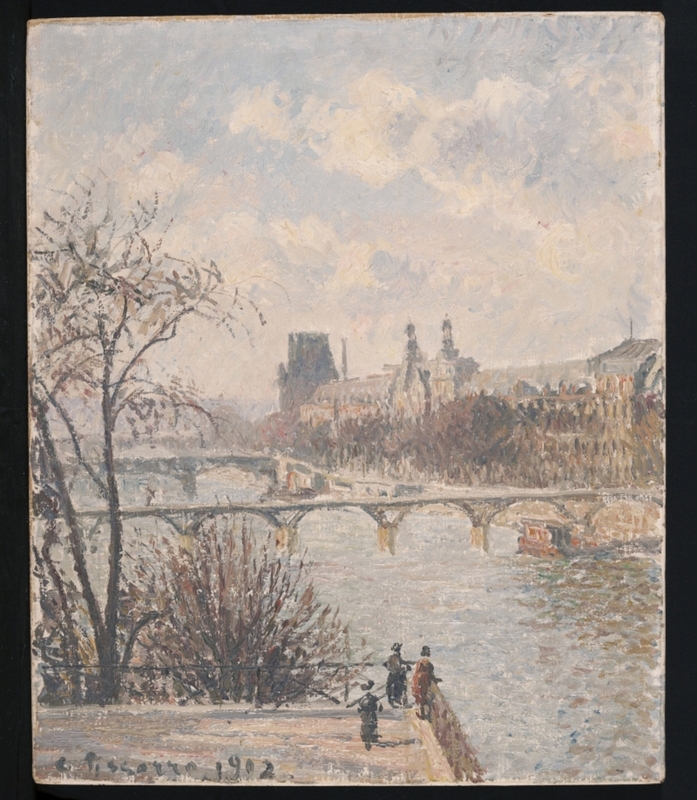

La Seine vue du Pont-Neuf, au fond le Louvre

This is a case of Nazi-looted art—this painting is one of the nine “red” cases in the Gurlitt collection, which was therefore restituted to the rightful descendants on 18.05.2017.

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) was a central figure in the development of Impressionism and later Neo-Impressionism,. In the final years of his career, around 1902, Pissarro returned to a more fluid and expressive painting style, moving away from the strict techniques of Pointillism. Hindered by an eye infection that prevented him from painting outdoors — plein air painting was a practice of central importance to the Impressionist movement, — Pissarro began depicting urban scenes from hotel windows—a practice that came to define this period of his work, marked by vibrant cityscapes such as views of the Pont-Neuf, rendered with renewed spontaneity and atmospheric warmth. In 1901, Pissarro returned to Paris for the winter and set to work on his second place Dauphine series, as he called it. Residing in his flat at 28 placen Dauphine from 31 October 1901 to 17 May of the following year, he painted no fewer than twenty-six oils from his window there (see nos. 1400 to 1425). One of them was “La Seine vue du Pont-Neuf, au fond le Louvre”.

The first owner of this painting was the public notary André Teissier of Mâcon, by whom it was acquired as a gift from the artist in 1902. The work subsequently passed to Galerie de L’Élysée, the dealership owned by Jean Metthey, and thereafter to the French collector Gaston Lévy (1893–1977). Lévy was the co-founder of the Monoprix retail chain and an enthusiastic collector of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists. The painting was later acquired by Lévy’s partner at Monoprix, Théophile Bader (1864–1942). Bader and his cousin Alphonse Kahn were the co-founders of the famous department store Galeries Lafayette. Bader’s daughter Paulette was married to Max Heilbronn (1902–1998), who became the next owner of the painting. Following the Nazis’ invasion of France in 1940, Galeries Lafayette was “Aryanized” by the Nazis, displacing Jewish owners like Théophile Bader, Raoul Meyer, and Max Heilbronn, along with 129 Jewish employees. The property of both the Bader and Heilbronn families became subject to confiscation.

Heilbronn and Meyer resisted Nazi oppression, with Heilbronn, a reserve captain, devising the Green Plan to sabotage the French railway network. He was arrested on June 12, 1943, by the SS's Sicherheitsdienst and imprisoned in several camps, including Buchenwald, from which he was liberated on April 30, 1945. Max Heilbronn, who was active in the French Resistance, was arrested in Lyon in 1943 and deported first to Buchenwald and thereafter to Dachau.

In an attempt to protect the family’s assets, Paulette Heilbronn in 1940 deposited the most important of the family’s artworks for safekeeping with Crédit Commercial de France, at the bank’s Mont-de-Marsan branch. At an unknown date prior to 13 February 1941, the Heilbronn bank vault was opened by the German Devisenschutzkommando and its contents were seized by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) - a Nazi Party organization dedicated to appropriating cultural property during the Second World War. This Pissarro painting was entered into the ERR inventory as property of Ms. P. Heilbronn on 18 July 1942.

On 31 October 1942, the work was subject to an exchange of the ERR with the German art dealer Gustav Rochlitz. Rochlitz engaged in active exchange of artworks with agents representing Göring, who refused to purchase from Rochlitz and instead provided him "degenerate" art in exchange for Titian and other Old Master works. These "degenerate" artworks primarily comprised French paintings from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, that "would under no circumstances be taken to Germany...but would be burned". In the course of 18 exchange transactions, Rochlitz received 82 confiscated paintings. In his interrogation report of August 15, 1945, the Pissarro work was considered lost.

However, as stated in the Gurlitt Provenance Research Project report, in April 1945, the painting is thought to have been sent by Rochlitz to his storehouse in the Bavarian town of Buching, near Hohenschwanggau. It is not clear how or when the work entered the Gurlitt collection.

After the war, the Heilbronn family registered a claim for the painting with the French authorities. The case was closed on 5 August 1961, when the whereabouts of the painting were not known. The work remained in the Gurlitt family collection until 2014, before being successfully returned to the heir of the former owner in 2017. This painting became the fourth case of restitution of items from the Gurlitt collection.