Group 4: Virtual Exhibition

(Im)mobile Objects

Introduction

In this virtual exhibition, we present two case studies from Swedish institutions:

The ancient petroglyphs preserved by the Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (SHFA): immobile carvings located on remote cliffs, now rendered digitally accessible.

The Royal Coronation Carriage at the Royal Armory : a once highly mobile object used in state ceremonies, now permanently still.

Together, these examples raise questions like:

- Who decides whether culture should move or remain still?

- Is digital heritage truly democratic, or does it reproduce old power structures in new forms?

- How can we understand the value of heritage when it exists between movement and stillness?

This exhibition invites you to reflect on those questions.

Svenskt Hällristningsforskningsarkiv's

[Swedish Rock Art Research Archives]

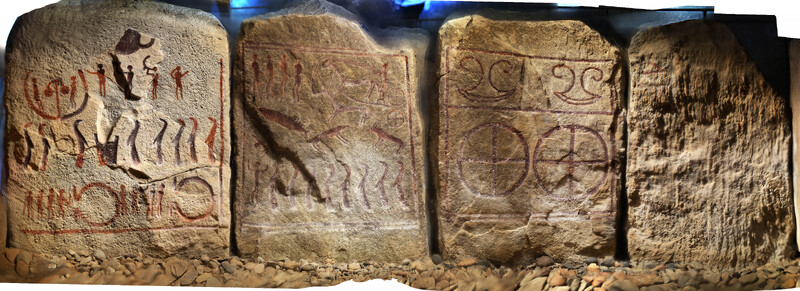

Moving to new locations and discovering unfamiliar areas is a deep longing in every adventurous person. By staying still, we do not encounter anything new. That was the case—until digitization, which now makes artifacts and stories just a click away on a computer or phone. With this, we can easily trace the earliest depictions of transportation, such as those found in rock art dating back to the Stone Age. Many of these petroglyphs can be found on rock faces along the Scandinavian coast and date to various periods of the Bronze Age. The most common motifs are boats and foot soles, revealing a strong desire for movement and exploration. In this exhibition, we will focus on one grave containing such carved images, found in Kivik, Sweden. This grave, known as The King’s Grave (Kungagraven) with the place number L1990:6549, is extraordinary—equipped with stone slabs that portray a moving story, including one of the only known depictions of a horse-drawn carriage, often interpreted as a chariot.

These motives depicting movement have been chosen to be portrayed on an immovable canvas, mountains and rock faces that barely even nature could move. The carriages, the boats, and the foot soles are stuck in place never moving standing in the same place they did 2000 years ago. In another viewpoint, they are constantly stuck moving. Movement in stillness.

The King's Grave is a stone cist that was discovered inside of a stone cairn when the local people were searching for stone to use for their properties and farms. The grave features in total 8 stone slabs decorated with rock art but we will focus mostly on slab 7 and also slab 8. Slab number 7 features the famous chariot that can be found in the stone's top right corner. The Scandinavian bronze age was a time of discovery and travel with the first major overseas trades and intermarriage with bridal offerings from far away countries, coppar was not found naturally in Sweden and so travel was necessary to attain the most important metals of this time. This chariot was most likely done from a southern influence and is showcasing the great valor in transport and the pride to be found.

Being located in a grave, this slab is often interpreted in a funerary context showing a man's death, or his descent from the living to the Godly world. The "birdmen" shown in the bottom appear to guide this man to his rightful place, his final resting place. The above scene showing the chariot and hunting is interpreted to be either the man while living or the Godly afterworld waiting for him above. Slab number 8, positioned on the left side of slab 7, is interpreted as a funeral with the birdmen laying a pot into his grave with hornblowing men above. These birdmen are interpreted to have had an important ritual role, either priests/priestesses or mythical creatures aiding in death. We can see that these depictions are showing a movement from the living to the dead, on this immovable canvas.

Although the man is dead, the stone will survive and is still standing today after 2000 years. In a place of final rest and stillness it was important to show the greatness in movement. However, not even a grave is a still place since in this grave 5 different individuals have been buried during the different periods of the bronze age, the dead bodies have therefor been moved around to make room for the newly deceased. This grave, being buried inside a cairn, was not meant to be easily accessible and it would take effort everytime a new individual would be buried. Death was not the end, but a journey that kept living. The chariot depiction could showcase a vehicle used by the dead to travel beyond the land of the living into the unexplored land of the dead. This journey and movement was important to depict in stone that would last as long as the skeletons lay in the grave and for every person that had to open up the grave to add another man.

These individuals were layed during a 600 year old period during an everchanging bronze age and stone allowed for memories to never be forgotten. Time has moved on since the creation of The King's Grave, over 2000 years, but the bronze age continues to live through these immovable stones. The very medium used to express travel and transition cannot itself be transported. Stone was chosen for these depictions of travel to preserve what was fleeting. Chariots decay, footprints fade, humans die, but a carving in stone can endure for millennia.

Livrustkammaren

[The Royal Armory]

The Coronation Carriage

In 1696 the Royal Stables in Stockholm burnt down and many of the royal carriages were destroyed. Right afterwards an order was placed by king Karl XI for a new carriage from France. The architect Nicodemus Tessin the younger would act as the one in charge of this order, sending it to the ambassador in France Daniel Cronström. The carriage was going to be designed by Jean I Berain. After 14 months of work the carriage was finished and it was sent to Stockholm. Between the time of the order and the finished carriage the old castle had burnt down and the king had died. The first time the carriage was used was between the marriage of Fredrik IV of Holstein-Gottorp and king Karl XI:s daughter Hedvig Sophia. But it wasn't until 1751 it was modernized into the version that we can see today.

In 1751 the first double coronation was going to take place. It was between Adolf Fredrik of Holstein-Gottorp and Lovisa Ulrika of Prussia. Lovisa Ulrika would use the carriage and Adolf Fredrik would ride on a horse to the coronation in Stockholm. The carriage now changed its warlike attributes from the 1600s and instead became more ”peaceful”. The one to oversee these changes would be the architect Carl Hårleman who would be among the best decorative artists of the mid 1700s in Sweden. The sculptural parts of the carriage were made by the woodcarver Adrian Masrerliez, the decorative paintings on the exterior by Johan Pasch and the fabrics designed by Jean Eric Rehn.

The Museum of The Royal History of Sweden

The Royal Armory could be traced back to the 1500s and to the time of king Gustav Vasa. The king decided to organize the royal administration into different chambers. These would be the chamber of the household, the royal wardrobe, the royal armory and the royal mews. These were all housed in the castle in Stockholm. The armory began to form into the collection we can recognize today when the armory and the arsenal were combined during 1803. Later on other collections joined the royal armory like the royal wardrobe and equestrian equipment from the royal stables. During the 18th century the royal weapons had become private, separate from the royal armory which meant that these could be sold or given as gifts. Later on many of these would eventually be deposed in the royal armory. Kings like Karl XV and Gustav V would give their collections to the royal armory. During the late 19th century the Royal Armory would form into a modern museum or what we could recognize as a museum today.

The purpose behind the collection starts in the 1600s. King Gustav II Adolf would include into the royal armory two suits he wore during the war against his cousin Sigismund. In 1627 the king was shot twice during his campaign in Prussia. The garments were then in 1628 displayed in the Royal Armory and preserved ”as a perpetual memorial”. In many was the Royal Armory, the museum of Swedish Royal history still functions in the same way, to preserve the memory of the kings and queens. During the mid 19th century the collection was turned into a museum to govern nationalistic and royalist sentiments among its visitors. In the 1900s this would change into a more scientific purpose with focus on research rather than nationalistic romanticism.

The Location

The Royal Armory has moved a lot during its history. The Royal Armory was first located in the Castle in Stockholm. During the 1600 it moved out of the castle to nearby buildings. The armory moved first to the Summerhouse in Kungsträdgården (the king's garden) and then to the Palace of de la Gardie, also known as Makalös (Unequalled). The armory then moved to Fredrikshovs castle when Makalös was going to be used for the Royal Dramatic Theatre. Then in 1803 the armory moved back to Kungsträdgården but to the Orangery. That building proved to be unsuitable for the expensive textiles and the collection was dispersed. The collection was then united again and this time the royal armory moved into the Heir Apparent’s Palace which today is used by the Swedish Government as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Royal Armory was supposed to move into the new Nationalmuseum building 1865. The collections proved to be too large to house in the building and in 1885 the Royal Armory moved into the Castle. Then in 1906-1907 the objects were moved once again to the Nordic Museum which functioned as the location up until 1978.

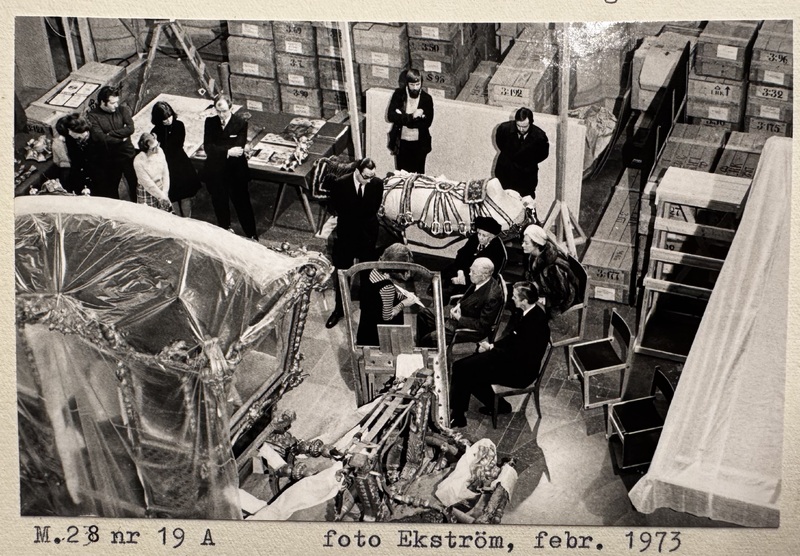

In 1965 the Swedish Exhibition Agency was formed as a government agency under the Swedish Ministry of Culture. During this time it was decided to explore the possibility of moving the Royal Armory to the Castle again. The museum moved back to the castle in 1978.

The Final Destination

The last time the coronation carriage was used was during the coronation of king Karl XV and Queen Lovisa of Netherlands. Karl XV died without a male heir which meant that the crown was passed on to Oscar II and his coronation would be the last one to take place in Sweden. It was decided to not use the carriages for the coronation and this meant that they would become museum objects. The carriages that are on display in the Royal Armory today also proved to lack the modern comfort of the newer carriages and coaches that could be used by the Royal Family. It was decided in 1884 that the carriages from the 1600s and 1700s would be transferred to the Royal Armory. The carriages were displayed in the north western side of the castle, where Bernadotte library is today. When the armory moved to the Nordic Museum the carriages would be transported for the last time on their own wheels. When the Armory moved out from the Nordic Museum in 1978 they would be transported on trucks to the castle. In 1969 they tested the current day location in the castle by creating dummies of the carriages which were built in place. For the carriages to be able to fit into the castle they opened up a hole in the wall and rolled down the carriages and the hole was then sealed.

The current exhibition down in the carriage hall has changed little. There used to be more objects on display next to the carriages and there was a small area with one big glass display in the end of the hall that would for many years function for smaller temporary exhibitions. In 2018 this was the only exhibition area open because of the new permanent exhibition. After the main exhibition area was finished, conservation work was done to the carriages and a new exhibition in the carriage hall was finished. The carriages didn’t change place, that would require the same procedure as before and instead the framing of the carriages was changed. The area mainly dates from the 1700s and has a focus on the coronation of Adolf Fredrik and Lovisa Ulrika. This gives the coronation carriage a context. The visitors will not only see the carriage, they will also be able to see the dress of the queen who would use the carriage and an old textile used in the carriage before 1751.

Will this be the last destination of the Coronation carriage? At the moment there are no plans of moving the royal armory or the carriages so for now this is the final place of the carriage. For the carriage to be moved they will need to remove the wall of the castle and that’s something that will not happen in a very long time.

You have reached the end of the virtual exhibition!

We would like to thank you for your visit and hope that you have been inspired to reflect and think differently about mobility and immobility of objects, goods, people, ideas, cultures and knowledge in general and in the digital age in particular.