Group 2: Vanilla Exhibition

A Global History of Vanilla: Plant, Spice, (colonial) Commodity

The Vanilla family (genus) includes over a hundred different orchid species, with shrinking numbers (see Housholder (2010) Herbology Manchester (2016), Karremans et al. 2020). The most commonly known one Vanilla, the second most expensive spice in the world, is the Vanilla planifolia, it is a tropical orchid native to Mesoamerica. Its cultural use goes back to the Totonac people of eastern Mexico, they were the first to cultivate and flavor food with vanilla. Later it was used by the Aztecs,who demanded it as a form of tribute, and who used it to enrich cacao-based drinks (Herbology Manchester (2016)) The plant itself is an epiphytic vine, requiring specific ecological conditions and a pollinator—originally, the Melipona bee in its native range—for fertilization ((Herbology Manchester (2016))

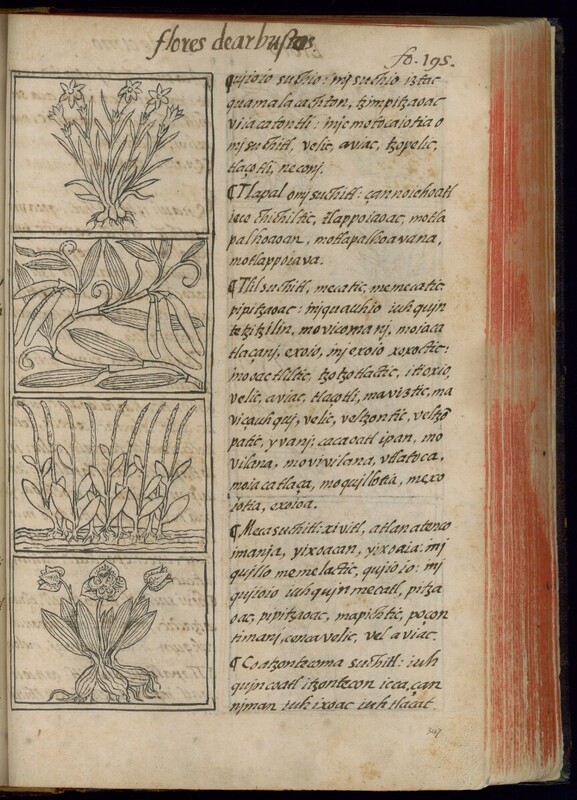

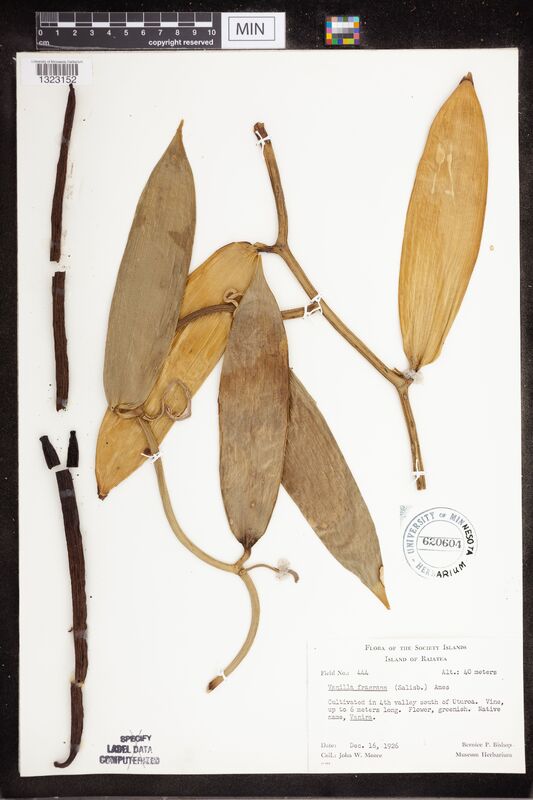

Vanilla’s journey as a global flavor began with colonialism.One testament for this can be found in the Florentine codex from the latter half of the 16th century. When the Spanish brought it to Europe in the 16th century, it was initially a curiosity, later growing in popularity. Attempts to grow vanilla outside Mexico initially failed due to the lack of natural pollinators. This changed dramatically in 1841, when Edmond Albius, a 12-year-old enslaved boy on Réunion Island, discovered a hand-pollination method.(Shermann 2022) His innovation allowed vanilla cultivation to flourish across colonial plantations in Réunion, Madagascar and the Comoros, deeply altering global production and the economicvallue of vanilla. Due to the economic interest in vanilla, many scientific institutions, such as Universities, in the Global North collected specimens of Vanilla planifolia. They either dried them for their herbarical collections (see image 2 and 3 in our exhibition) or cultivated them in their botanical gardens (see picture 4). Even so, in recent years some botanical research claimed that there is a lack of collections of the Vanilla Genus, except for planiflora. This is because of the popularity of Vanilla planifolia, the preservational and logistical challenges of creating dry herbar specimens and the short flowering period of the plant. Resulting in taxonomic problems and only narrow genetic information. Recent studies stress the need to preserve and research the natural biodiversity of vanilla species. (2010) and Karremans et al. (2020)). Therefore digitalisation of Vanilla specimens can be twofold important:

- It allows knowledge sharing and a comparative Study of Specimens (Karremans et al. (2020)). This is important for herbars, because there is a structural inequality rooter in colonial past, in the information distribution (see Park, 2023)

- It may allow us to overcome some challenges of collecting the flowers for taxonomie by generating for example 3d models of the plant. However field research stays important for elements like smell and genetic samples. In the best case this gives some data source and leverage to the origin places of the plant.

Vanilla is now the world’s second most expensive spice after saffron, due to the labor-intensive hand-pollination process and long curing time required to develop its characteristic aroma. Chemically, the flavor is dominated by vanillin, though true vanilla includes hundreds of compounds contributing to its complexity. The development of synthetic vanillin from lignin and petrochemicals in the 19th and 20th centuries industrialized the flavor but further complicated the economic landscape, often undermining natural vanilla farmers.

The global vanilla industry remains shaped by colonial legacies. Madagascar, once a French colony, produces about 80% of the world’s supply, and its economy is tightly bound to volatile global markets. Vanilla farming here is marked by economic precarity, deforestation, and exploitative labor practices, a contemporary echo of its colonial past.

To learn more about the vanilla industry you can watch this video from Business Insider

Digitalising Plants

Digitalising plants is challenging. Most efforts so far have focused on taking high-resolution photos of plants, whether they’re pressed and dried in herbarium collections, preserved in liquid, or still growing in gardens or their natural habitat. But this approach has its limitations. Photos only capture a plant from one angle at a single moment in time. They often fail to convey spatial information or a sense of scale. On top of that, many important details are lost, such as how the plant feels to the touch, how it smells, or how it changes throughout its life cycle.

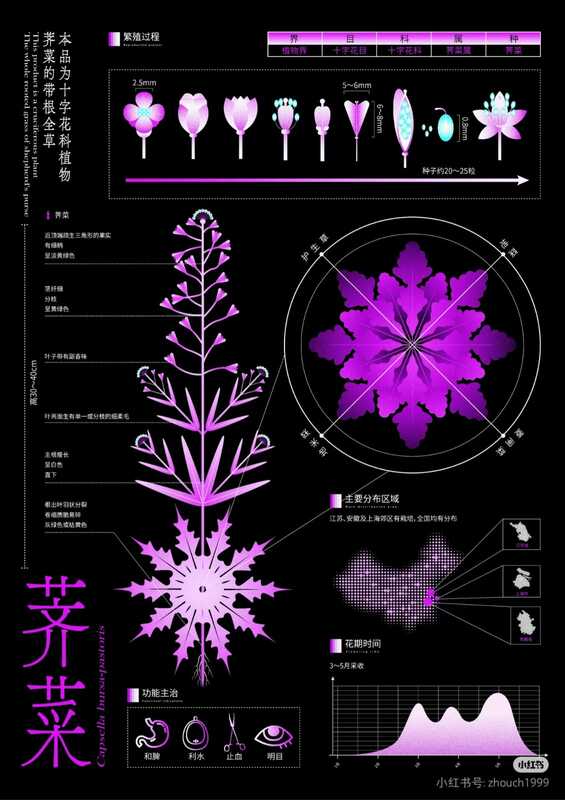

However, there are ways to complement traditional digitalisation methods. Two examples are shown here, both using plants other than vanilla. The first is a highly stylised drawing that shows different stages of the plant’s growth. It doesn’t aim to be lifelike but instead represents the plant in a symbolic, illustrative way. The second example uses video to visualize a styliezed 3D model of a whole plant, its flower and its fruit. Suplemented is this with a sothing track, which tries to encite some of the feelings one might have while engaging with the plant in Person.

Both examples offer a different approach to digitalise plants, while also being themselves limited by the same constraints as before. They are also no alternative to pictures of the real plants, as both employ artistic license to offer a different angle on the plant, which does not necessarily aim at realism. But they do achieve to better convey the beauty and the emotions one feels when seeing a Plant.

Digital Vanilla

Touch, Print, and Take the Plant Home

Our 3D vanilla models invite you to explore Vanilla planifolia beyond the page or herbarium sheet. These digital objects were generated from botanical references using AI and cleaned for better visual and tactile interaction. They are not exact replicas—but poetic reconstructions of how humans see, collect, and remember plants.

Download in sketchfab

Bring a Plant Home

How can a digital plant grow in your world?

At PlantsThatMatter, we believe that plants don’t just live in gardens or archives—they live in our stories, classrooms, memories, and now… maybe on your desk. Here are two ways to bring part of the vanilla plant into your life—digitally or physically:

Download the 3D Version

Step into the virtual herbarium.

Our 3D vanilla model is ready for you to explore, remix, print, or animate.

You’ll get:

- A detailed 3D model of your favorite plant (STL & GLB)

- Ready for 3D printing, virtual modeling, AR, or creative play

- Free to use (non-commercial license)

Try it in your way:

→ [Download Plant_v1.stl]

→ [Open in Blender]

→ [View in AR or import to your app]

Color Your Own Plants

Prefer something hands-on?

We made a simplified version of the model that’s perfect for printing at home—or ordering from us. It’s blank, smooth, and just waiting for your imagination.

Great for:

- Painting with kids or friends

- Creative workshops

- School activities

- Adding a personal touch to your shelf

Use markers, paint, even natural dyes!

→ [Order a ready-to-paint 3D plant]

Share Your Plants

Painted your version? Placed the vanilla on your desk? Tag us with #PlantsThatMatter or upload to our community gallery.

Every plant tells a story. Let’s tell the next one together.

Sources:

- The Sherman (2022): Edmond Albius and the Story of Vanilla — link

- Wikipedia: Vanilla, Vanilla planifolia

- Kew Gardens: Plants – Vanilla — link

- Herbology Manchester (2016): Advent Botany – Day 23: Vanilla — link

- Householder et al. (2010): Diversity, Natural History, and Conservation of Vanilla in Amazonian Wetlands of Madre de Dios, Peru, Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas — JSTOR

- Karremans et al. (2020) A reappraisal of neotropical Vanilla. With a note on taxonomic inflation and the importance of alpha taxonomy in biological studies Lankesteriana, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 395-497. — link

- Park, Colonialism has shaped scientific plant collections around the world – here’s why that matters, in: The Conversation, 12.06.2023. — link