Found

These artworks from the Gurlitt Collection were recovered during its rediscovery with either partial or uncertain provenance, meaning that their histories are neither fully lost nor fully understood. Though not definitively classified as looted, they remain under scrutiny and are caught in limbo between recovery and resolution. This section brings together pieces that have resurfaced from decades of hiding and are now made visible as part of ongoing efforts to clarify ownership and confront the legacies of wartime displacement.

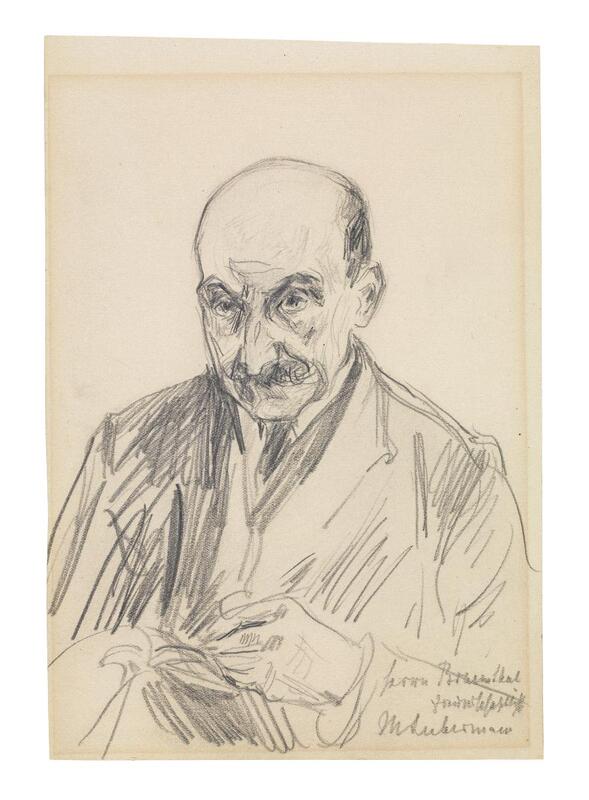

'Mother with Dead Child' by Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), c.1903

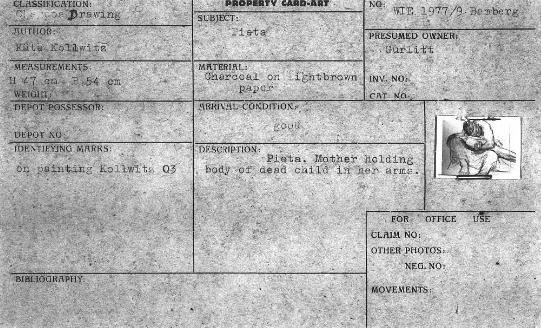

Käthe Kollwitz’s Mother with Dead Child (c.1903), sometimes known as Pietà, is an intimate, haunting depiction of grief predating the artist’s own loss of her son Peter during the First World War. This work, now held in the Stiftung Kunstmuseum Bern as part of the Gurlitt Estate, is part of a series depicting Kollwitz’s struggle through grief. Although it is not listed as obviously looted, its ownership between 1933 and 1945 remains blurry and no clear documentation for how Hildebrand Gurlitt acquired it was provided.

Kollwitz was an influential German artist and the first woman elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts. Her work frequently engaged with universal human experiences such as the suffering of the working class, war, and mourning, which drew attention from admirers and critics alike. Despite her fame, Kollwitz’s artwork was labeled ‘degenerate’ and ‘unpatriotic’ by the Nazi regime for her political beliefs and forced to resign from the Academy. Her work was removed from museums and she was banned from exhibiting, though the Nazi Party did use her pieces ‘Hunger’ and ‘Bread!’ as propaganda during the war. Kollwitz and her husband were threatened by the Gestapo with deportation to a concentration camp, however it is likely due to her renown that this was never realized. She fled from Berlin shortly before her home was destroyed in 1943, where a large part of her artwork was destroyed. She died just 16 days before the end of the war with her life’s work scattered or lost to war.

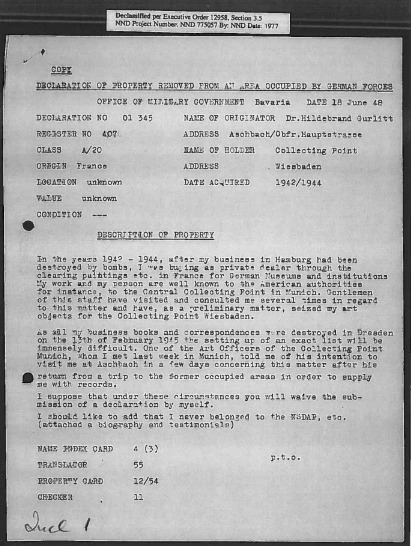

The work’s provenance remains partially obscured during the war, meaning that Gurlitt likely acquired Mother with Dead Child either from Kollwitz directly or during the confiscation of her work from museums. Although there is no clear evidence of looting, the lack of legal documentation does not end the uncertainty surrounding its possession. Seized in 1945 and registered under WIE 1977/9, the drawing was held at the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point until 1950 under suspicion of illegal acquisition and Gurlitt himself was brought for interrogation by the so-called ‘Monuments Men’. Despite suspicions, the collection was returned to Gurlitt after he presented affidavits listing how he acquired each piece. The Kollwitz drawing was labeled with a +, suggesting that it came from the artist directly or at the very least not taken from a Jewish collector. The mounting political pressure to close the collecting points following the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany and law requiring the restitution of property to German citizens, Gurlitt’s affidavits were accepted without further investigation.

Until its rediscovery as part of Cornelius Gurlitt’s estate, Mother with Dead Child had essentially vanished. Digitized property cards and the archived Wiesbaden records were the only traces of this piece, a faint reproduction attached to an inventory list. This context makes its digitization and visibility today particularly significant. The digital copy offers the only means of engaging with a work that was presumed lost for decades, and although Kollwitz created several other pieces that mirror it, the composition and the emotions it evokes are singular. There is a sort of vulnerability existing within this piece that is not captured in its sister-works. The open sole of the foot, unfinished details, and layered sketching gives a sense of unfulfilled potential and raw grief that is much more present in this version of Kollwitz’s mourning series. As part of the digitized Gurlitt estate, this work is known not only as an expression of personal loss, but also as an expression of the grief associated with erasure and displacement under the Nazi regime. In this form, Mother with Dead Child is a symbol of survival and memory made possible through digitization.

Sources:

'Kollwitz Timeline - Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln', n.d., Startseite – Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln., https://www.kollwitz.de/en/kollwitz-timeline

'The Art of Contradiction: Nazi Reception of Käthe Kollwitz: Broad Strokes Blog', 2021, National Museum of Women in the Arts., https://nmwa.org/blog/artist-spotlight/the-art-of-contradiction-nazi-reception-of-kathe-kollwitz/

Foundation, M.M., 2013, 'Update on the Cornelius Gurlitt Collection', MonumentsMenWomenFnd., https://www.monumentsmenandwomenfnd.org/post/update-on-the-cornelius-gurlitt-collection?srsltid=AfmBOorj75c9JiLOFINLIAt-pdZFub7cTZHUBEDlO1nuAkBcuFbIcE_K

'Gurlitt Case ', n.d. Hildebrand Gurlitt: Allied Documents, Interrogation and Collection List 1945-1950, https://www.lootedart.com/QDES4V964951

'Supporting Documentation Provided by Gurlitt', n.d., Hildebrand Gurlitt: Allied Documents, Interrogation and Collection List 1945-1950, https://www.lootedart.com/web_images/pdf2013/Supporting%20documentation%20provided%20by%20Gurlitt%20and%20related%20documentation%20from%20the%20Allies%20regarding%20the%20collection.pdf

'EU, Ardelia Hall Collection: Wiesbaden property cards, 1945-1952', n.d., Fold3, https://www.fold3.com/image/231912408/wie-19779-page-1-eu-ardelia-hall-collection-wiesbaden-property-cards-1945-1952

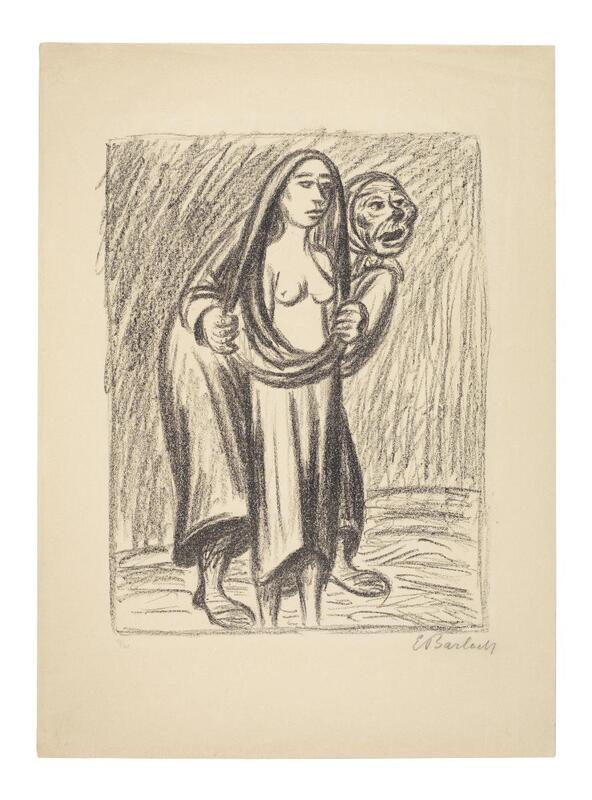

'Das Opfer (Die Kupplerin)', by Ernst Barlach (1870-1938), c.1924

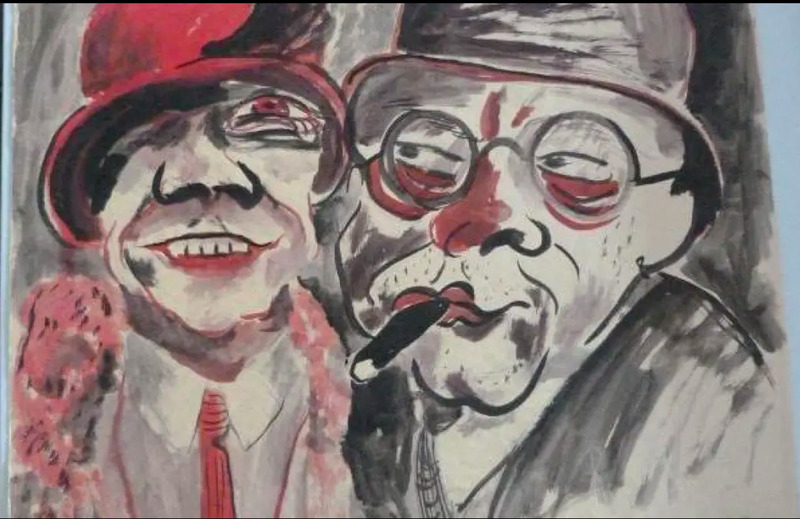

Ernst Barlach (1870–1938) was a German sculptor, printmaker, and writer whose expressionist works grappled with themes of suffering, spiritual depth, and the human condition. Although widely acclaimed in the Weimar period, Barlach’s art was later condemned as “degenerate” by the Nazi regime, which saw in his introspective, anti-militarist sculptures a powerful challenge to its ideological narrative. While Barlach is primarily recognized as a sculptor, the artist also practiced graphic art, exhibiting a distinctive and readily identifiable style. His works from the 1920s are distinguished by deliberately rapid, seemingly uncontrolled strokes, which convey the grotesque expressiveness of the scene.

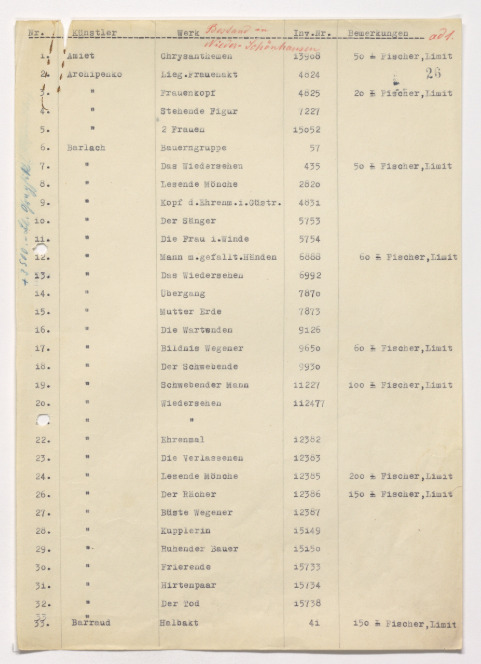

Among the three graphic works by the artist found in Gurlitt's collection, the lithograph "Das Opfer (Die Kupplerin)" is of particular interest. It is classified as a yellow-green object in the collection with a partially unidentified provenance.

Three more copies of this lithograph can be found in the Degenerate Art database, and the provenance of all four is linked to confiscation period of August – October 1937 - In 1937, Adolf Hitler ordered the directors of museums and collections in the German Reich to hand over works of art that were considered “degenerate” according to Nazi ideology. As a result, more than 21,000 art objects were confiscated, including paintings, sculptures, and prints. The print from the Gurlitt collection is the only one of these that has been found to date.

During 1938 and 1939, the work was stored at a “depot for internationally usable art” in Berlin (Depot Schloß Schönhausen Lagerung "international verwertbarer" Kunstwerke), where works that were not exhibited at the propaganda show Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) were housed. On 22.05.1940 , among many other works of art, it was purchased by Hildebrand Gurlitt for his gallery in Hamburg. This is indirectly confirmed by a document stating that in October 1939, a large part of the graphic art collection was sent from the storage facility to Gurlitt for review and further purchase, and by January 1940, a purchase offer was requested. This work is not included in the purchase lists, but it is mentioned in the later inventory list of the collection. The work remained in the Gurlitt family collection until 2014.

In the final years of his life, Ernst Barlach was purposefully erased from art history - his sculptures were dismantled and destroyed, reliefs of his work were removed from buildings, 381 of his works were seized from museums. Presently, it remains imperative to reestablish his position in the historical context of art.

Sources:

Brief, Rolf Hetsch - Hildebrand Gurlitt, 18.12.1939, Händlerakte Gurlitt, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R 55/21015; Vertrag, Kauf, Deutsches Reich - Hildebrand Gurlitt, 22.05.1940, Händlerakte Gurlitt, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, R55/21015, Bl. 168, https://invenio.bundesarchiv.de/invenio/direktlink/9de9ebf7-dd56-482b-b8a6-8443b0cd3868/.

Kunstmuseum Bern. “Ernst Barlach: Das Opfer.” Gurlitt Art Trove | Kunstmuseum Bern, https://gurlitt.kunstmuseumbern.ch/en/collection/item/154197/.

Forschungsstelle "Entartete Kunst", Kunsthistorisches Institut der Freien Universität Berlin. “Ernst Barlach, Das Opfer”, http://emuseum.campus.fu-berlin.de/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ResultDetailView/result.tab.link&sp=13&sp=Scollection&sp=SfieldValue&sp=0&sp=1&sp=3&sp=SdetailView&sp=2&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=T&sp=0&sp=SdetailView&sp=0&sp=SdetailBlockKey&sp=2#this().

Ernst Barlach Haus, https://www.barlach-haus.de/en/ernst-barlach/biography/.

Untitled (Two riders on the beach), by Max Liebermann (1847-1935), c.1901

This 'Reiter am Strand' painting received much less attention than the other more well-known one, as its last known owner before World War II was the painter himself, Max Liebermann. However, as with many works in the Gurlitt estate, it being stolen art can not be excluded. Its ownership during the war remains untraced, and the painting only resurfaced in 1953 when German art merchant Hans Helmuth Klihm sold it to Hildebrand Gurlitt.

Klihm is suspect himself, as he worked closely with Walter Bornheim, who trafficked in looted art on behalf of Hermann Wilhelm Göhring. During the war, Göhring largely withdrew from his military responsibilities and devoted his time to collecting artwork and property, most of which was stolen from Jewish victims of the Holocaust.

Similarly, many works passed through questionable hands during the war, though some may have been acquired through the official channels of the art market. This case reflects a broader challenge in provenance research, as the painting passed through so many well-known art traffickers associated with the Nazi regime that it raises unresolved ethical concerns over its acquisition.

Untitled (self-portrait with the sketchbook), by Max Liebermann (1847-1935), undated

This sketch can be linked to the Jewish merchant Max Julius Braunthal through the note "Herrn Braunthal freundschaftlich MLiebermann" on the back. Due to the inscription and their known friendship since WWI, its was likely a gift from the artist to Braunthal. As a Jewish collector, Braunthal faced persecution by the Nazi regime and in 1941, was stripped of his German citizenship along with his wife Lotte and three children. After this, his fortune and assets were seized by the Nazi regime as 'forfeited to the Reich'. This was a fate shared by many Jewish collectors and merchants during this period.

During the war, Max and Lotte were arrested and held in Drancy and later Gurs internment camps, where many Jews were held before being deported to German concentration camps. Due to their friendship with Jean Guilleminot, a police commissioner in Neuilly-sur-Seine, Max and Lotte escaped deportation in 1944. Afterwards, they took refuge under false identies in Preval, a commune in northwestern France. However, the apartment they were staying at was confiscated and occupied by the Wehrmacht and French police from 17 June to 21 August 1944, and they lost many possessions.

The provenance research committee for the Gurlitt Collection was unable to determine how this self-portrait left Braunthal's collection and came into the possession of the Gurlitt estate. However, it was likely taken either during the seizure of their assets in 1941 or occupation of their French apartment in 1944, and eventually made its way into the hands of Gurlitt through the Nazi-approved art trade between France and Germany.

It is currently held at the Kunstmuseum Bern as part of the Gurlitt Collection inherited from Hildebrand's son, Cornelius, in 2014.

Sources:

'Projekt Provenienzrecherche Gurlitt', n.d., Bericht für http://Lostart-ID: 477935

'Max Braunthal, Proveana', n.d., Provenance Research Database', https://www.proveana.de/en/person/braunthal-max

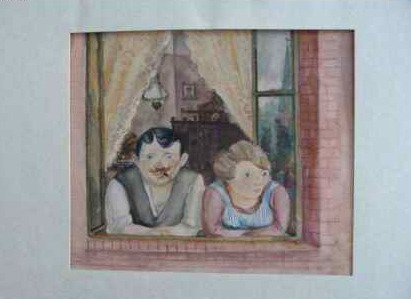

'Mann und Frau am Fenster/Man and Woman at the Window' by Wilhelm Lachnit (1899-1962), c. 1923

Mann und Frau am Fenster (Man and Woman at the Window), painted by German artist Wilhelm Lachnit (1899–1962), is a significant work from the early 20th century that reflects the stylistic and thematic concerns of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement. Lachnit, known for his expressive realism and social commentary, often depicted scenes of everyday life with psychological depth. This painting portrays a man and woman standing near a window, their postures and expressions suggesting tension, a common theme in Lachnit’s work, which frequently explored human relationships and social alienation.

The painting’s history is intertwined with the turbulent era of Nazi Germany, when the regime confiscated thousands of artworks deemed "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst) from museums and private collections. Many of Lachnit’s works were seized or destroyed during this period due to their modernist style and perceived ideological nonconformity. For decades, the whereabouts of Mann und Frau am Fenster were unknown, leaving it among the many "lost" artworks from the Nazi-era lootings.

In a remarkable turn of events, the painting was rediscovered as part of the controversial Gurlitt collection. This vast trove of art was hidden for decades by Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of Hildebrand Gurlitt, an art dealer who acquired numerous works under questionable circumstances during the Nazi regime. The collection, unveiled in 2012, contained over 1,500 pieces, including works by Picasso, Chagall, and other masters, who many suspected of being looted or sold under duress. Lachnit’s Mann und Frau am Fenster was among the identified pieces.

The rediscovery of the painting has allowed scholars to reassess Lachnit’s legacy and the broader impact of Nazi art theft. Today, Mann und Frau am Fenster stands as both an artistic achievement and a symbol of the unresolved legacy of looted art.

Sources:

Pound, C. (2017, 12 13). The Nazi art hoard that shocked the world. Hentet fra BBC, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20171212-the-nazi-art-hoard-that-shocked-the-world

'Mann und Frau am Fenster', n.d., Lost Art Database, https://www.lostart.de/en/found/object/mann-und-frau-am-fenster-man-and-woman-looking-out-window/477902

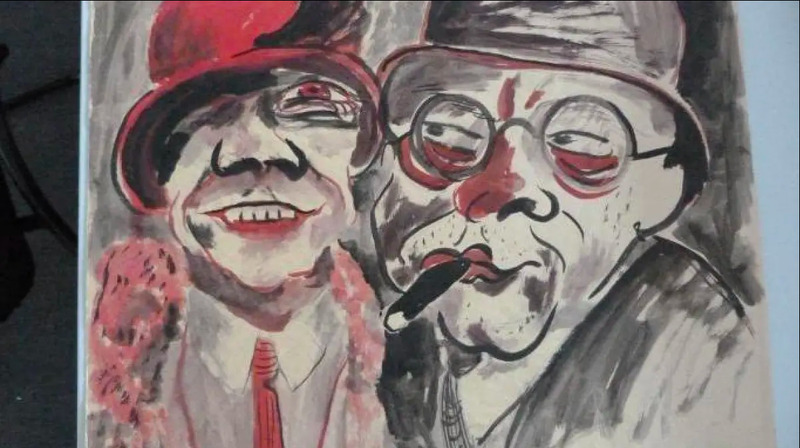

'Paar/Couple' by Hans Christoph (1901-1992), c.1924

Paar / Couple (1924), painted by German artist Hans Christoph, is a compelling work from the early 20th century that embodies the stylistic and emotional traces of post-World War I German art. Though less widely known than some of his contemporaries, Christoph’s work often explored themes of intimacy, melancholy, and the human condition, reflecting the broader existential anxieties of the Weimar Republic era. This painting, created in 1924, depicts a couple in a moment of quiet interaction, rendered with expressive brushwork and a muted color palette, characteristics that align with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement or the lingering influence of German Expressionism. For decades, the whereabouts of Paar / Couple remained unknown, leaving it among the thousands of works lost to history. The painting resurfaced as part of the sensational Gurlitt collection, the massive hoard of art discovered in the possession of Cornelius Gurlitt in 2012.

The rediscovery of Paar / Couple has sparked renewed interest in Hans Christoph’s work and the broader restitution efforts surrounding the Gurlitt collection. As efforts continue to return looted art to rightful heirs, works like Paar / Couple remain at the center of ethical and legal debates over cultural restitution

Source:

'Paar/Couple', n.d., Lost Art Database, https://www.lostart.de/en/found/object/paar-couple/477891

'Gurlitt Collection: Hoard of Nazi-era art set for Swiss Museum', 2016, BBC News Culture, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-38332637

'Sitting Woman' by Henri Matisse (1869-1954), c.1923

Henri Matisse’s Sitting Woman (c. 1923) is a striking example of the artist’s transition between stylistic periods, blending elements of his earlier Fauvist boldness with the refined simplicity that would later define his cut-out works. Created during a period of artistic reinvention, the painting likely depicts a model in Matisse’s studio, rendered with fluid lines, vibrant color contrasts, and a sense of intimate immediacy. Matisse’s fascination with form, posture, and the expressive potential of color is evident in this work, which exemplifies his ability to capture the essence of a figure with both energy and elegance. For decades, the origin of Sitting Woman was unclear, leaving its fate uncertain, until it also was identified among the controversial Gurlitt trove.

While its exact ownership history before the Nazi era remains under investigation, the painting symbolizes both Matisse’s enduring legacy and the shadow of wartime plunder. Today, as efforts continue to return looted art to descendants of its original owners, works like Sitting Woman serve as touching reminders of art’s vulnerability to political oppression.

Sources:

Eddy, M., 2015, 'Matisse from Gurlitt Collection is Returned to Jewish Art Dealer's Heir', The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/16/arts/international/matisse-gurlitt-collection-femme-assise-seated-woman.html

'Germany in deal to return Gurlitt's looted Matisse', 2015, BBC News, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-32053766